Time for the Sunday reading again, and I am so full of satisfaction that I have to repeat myself. For those of you who are new to this blog, I wrote a few months ago about my Sunday – horse-free – pastime at the cultural center where Marcel Proust is the main attraction on Sunday afternoons. We’re well into the third book of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. The fare is simple: a 10-15 minute recital by a top-notch musician and then the reading of a few chapters from Proust by a new reader every week.

The novel is autobiographical and told mostly in a stream-of-consciousness style. It includes collected pieces from his childhood, details, and fetishes of upper-class lifestyle, gossip, memories, and recollections of the world Proust never quite managed to join in late nineteenth and beginning twentieth century France. The leading motif in the book is of a past that has true reality for man. It is about the small intricacies and nothings of high-class society, with small intrigues, great ambitions and nebulous outcomes. It is a novel that takes time because it is about time. Memory and time are principal themes in the over 3000 page novel, and the situations, the characters, the surroundings are so basically human that you find yourself smiling and silently nodding in recognition as the characters evolve in the one social situation after the other. The upper class milieu is just an image of all of our human lusts, desires, shortcomings, fears and vanities.

I read another “extensive” book on the plane to the States a week or so ago. Praised by critics and acquaintances alike - Dan Brown’s: Angels and Demons. Excuse my English. It was crap. 619 pages of superficial, short episodes with no depth of character. Technical mistakes that a junior high school student wouldn’t make in an essay, and an irritating beating of the breast by the author for having done some basic research on paintings, buildings and people from historical periods, research that any author with self-respect would do to bolster a story. A word of humble advice. Get a copy of Proust's novel from your public library. Take a deep breath. Slow down a little and start reading. Or better yet: pair up – at home with your partner or with a friend - and read it aloud to one another. It will open up a new world.

For those of you wanting to give Proust a try, the first volume of Remembrance of Things Past can be found here. Try also Temps Perdu, a good site for Proust texts, for learning about the author and for more about his books.

December 26, 2005

Proust, Chapter 2

November 13, 2005

The thrill of it all

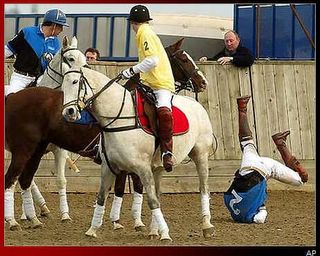

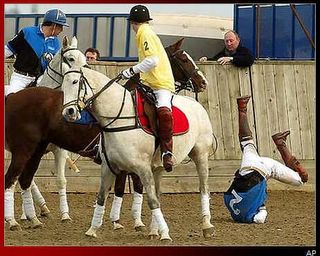

Riding is a dangerous sport, which is maybe why it’s so satisfying, tantalizing and both physically and emotionally edifying. Maybe motorcycling and skydiving qualify for a somewhat distant second place. Riding incorporates both skill, daredevilishness, communication with a large animal with a mind of its own and a thirst for well, not perfection, but getting better at it all. Now where else can you achieve that?

Falling off is no fun. There’s a common adage that says that you will never become a fully-fledged rider until you’ve fallen off a hundred times. Maybe a hundred times is pushing it, but most riders have fallen off at least a number of times and you learn from each and every experience, mostly because the one fall is never the same as the next. Getting thrown off in the woods because the horse gets spooked from a red plastic bag that some damn nature-loving mushroom picker carelessly threw away and hitting your shoulder on a rock that has spent the last 20,000 years just waiting to meet you is one thing. It’s a completely different thing riding towards a hurdle, keeping your eyes focused beyond the rail that you and your horse are going to jump, making a wrong decision like looking askance at the wrong moment or shifting your weight slightly, oh so slightly in the wrong direction and then getting thrown off in an extremely inglorious fashion. It’s a toss-up which is worse, the mistake that you made which was evident to most people looking at you, or the physical pain you suffer as a result.

Prince William falling off

Motorcycles and airplanes are machines. They usually don’t have a mind of their own, at least not outside the world of fantasy. But horses are like you and me. They go through infancy, childhood, puberty, adulthood and old age. Castor is 11 years old and should be an adult by this time, but he’s still in a somewhat pubescent stage and acts like a teenager. All of you who’ve had one around the house know what I mean: you never know what to expect and they eat enormous quantities of food. That's Castor in a nutshell.

But as in my case having parented a couple of teenagers, you know how to handle the unexpected. As far as my Castor is concerned, this means everything from jumping five feet to the side in a split second because he sees something as innocuous as his own reflection in the mirror in the manége or bucking gleefully, because it’s freezing cold and that’s the weather that makes him hyperactive. I think the weirdest accident I had was the concussion from getting thrown after a hurdle. I don’t know how I landed, but I didn’t get hurt... I jumped back on Castor and finished the series of hurdles I was doing. A while later I was standing in the stable calmly brushing him off when I realized I didn’t know where I was. I’d lost about twenty minutes of prime time with my horse and had no recollection of what we had been doing. But my friends told me I’d made several successful jumps in that space of time.

But it’s an individual you’re with. He’s got a mind of his own, legs of his own, muscles of his own and a temperament of his own, and that’s the thrill of it all.

So the moral of this blog post is this: Screw skydiving. Screw motorcycling and screw human catapulting. Get yourself a horse.

Falling off is no fun. There’s a common adage that says that you will never become a fully-fledged rider until you’ve fallen off a hundred times. Maybe a hundred times is pushing it, but most riders have fallen off at least a number of times and you learn from each and every experience, mostly because the one fall is never the same as the next. Getting thrown off in the woods because the horse gets spooked from a red plastic bag that some damn nature-loving mushroom picker carelessly threw away and hitting your shoulder on a rock that has spent the last 20,000 years just waiting to meet you is one thing. It’s a completely different thing riding towards a hurdle, keeping your eyes focused beyond the rail that you and your horse are going to jump, making a wrong decision like looking askance at the wrong moment or shifting your weight slightly, oh so slightly in the wrong direction and then getting thrown off in an extremely inglorious fashion. It’s a toss-up which is worse, the mistake that you made which was evident to most people looking at you, or the physical pain you suffer as a result.

Prince William falling off

Motorcycles and airplanes are machines. They usually don’t have a mind of their own, at least not outside the world of fantasy. But horses are like you and me. They go through infancy, childhood, puberty, adulthood and old age. Castor is 11 years old and should be an adult by this time, but he’s still in a somewhat pubescent stage and acts like a teenager. All of you who’ve had one around the house know what I mean: you never know what to expect and they eat enormous quantities of food. That's Castor in a nutshell.

But as in my case having parented a couple of teenagers, you know how to handle the unexpected. As far as my Castor is concerned, this means everything from jumping five feet to the side in a split second because he sees something as innocuous as his own reflection in the mirror in the manége or bucking gleefully, because it’s freezing cold and that’s the weather that makes him hyperactive. I think the weirdest accident I had was the concussion from getting thrown after a hurdle. I don’t know how I landed, but I didn’t get hurt... I jumped back on Castor and finished the series of hurdles I was doing. A while later I was standing in the stable calmly brushing him off when I realized I didn’t know where I was. I’d lost about twenty minutes of prime time with my horse and had no recollection of what we had been doing. But my friends told me I’d made several successful jumps in that space of time.

But it’s an individual you’re with. He’s got a mind of his own, legs of his own, muscles of his own and a temperament of his own, and that’s the thrill of it all.

So the moral of this blog post is this: Screw skydiving. Screw motorcycling and screw human catapulting. Get yourself a horse.

July 01, 2005

Responsibility and blame, murder and suicide

The subtle power of language influences our way of seeing the world around us. The words we use say a lot about us and our way of approaching a political and ethical reality.

Most of us are more or less in agreement on the meanings and connotations of the words in the title above. The word responsibility is often positively charged and relates to an individual’s various liberties and duties.

Oftentimes one can read something like the following in the media: “The organization XXX was responsible for the bomb attack which claimed four lives.” I think we have to re-think the meaning of this word. In a positive sense, being responsible is something we all strive for in many parts of our lives. Responsibility makes us grow as individuals. But being responsible for a crime or a misdeed sends a completely different semantic signal. In a negative sense, the word responsibility denotes a meaning of shame and blame. Subsequently, we should use the word blame when writing about actions such as the violent taking of lives in the many hotspots of the world. When a crime is committed it is a matter of blame, not responsibility.

Our societal norms and systems of justice make a distinct demarcation between murder and suicide. Within orthodox Christianity and Judaism they are both serious crimes against God. However, modern society perceives a decided difference between these two words. A vast majority of us think of murder as an infinitely more serious act than suicide, which in many cases is deemed almost a ”right” where an individual is master of his or her own rise and demise. Suicide is also often justified as a last-case outlet for depression.

When an individual extinguishes both his own life along with others, the label he is given by the media is that of a suicide bomber, or the deed is often described as a suicide bombing attack, a somewhat bizarre expression. But the words chosen in this context imply a conscious, value-related choice where suicide achieves primary importance (and in some odd way also becomes excusable and legitimate) and the murders committed as part of the same deed become peripheral with a spattering of anonymity. The reasoning, that one wishes to point out the fact that a person is willing to use his own body and life as a weapon, does not motivate the use of the term. A person who, in cold blood, kills both himself and others is a murderer, irrespective of what others think about and believe concerning the religious, ethical or political implications of suicide.

Certain media in the United States and other countries have begun using the correct term for these crimes: murder. Consequently, the young men and women who kill both themselves and others are homicide bombers – neither more nor less.

And those who hurt others to further their own cause do not bear responsibility, but instead blame.

Most of us are more or less in agreement on the meanings and connotations of the words in the title above. The word responsibility is often positively charged and relates to an individual’s various liberties and duties.

Oftentimes one can read something like the following in the media: “The organization XXX was responsible for the bomb attack which claimed four lives.” I think we have to re-think the meaning of this word. In a positive sense, being responsible is something we all strive for in many parts of our lives. Responsibility makes us grow as individuals. But being responsible for a crime or a misdeed sends a completely different semantic signal. In a negative sense, the word responsibility denotes a meaning of shame and blame. Subsequently, we should use the word blame when writing about actions such as the violent taking of lives in the many hotspots of the world. When a crime is committed it is a matter of blame, not responsibility.

Our societal norms and systems of justice make a distinct demarcation between murder and suicide. Within orthodox Christianity and Judaism they are both serious crimes against God. However, modern society perceives a decided difference between these two words. A vast majority of us think of murder as an infinitely more serious act than suicide, which in many cases is deemed almost a ”right” where an individual is master of his or her own rise and demise. Suicide is also often justified as a last-case outlet for depression.

When an individual extinguishes both his own life along with others, the label he is given by the media is that of a suicide bomber, or the deed is often described as a suicide bombing attack, a somewhat bizarre expression. But the words chosen in this context imply a conscious, value-related choice where suicide achieves primary importance (and in some odd way also becomes excusable and legitimate) and the murders committed as part of the same deed become peripheral with a spattering of anonymity. The reasoning, that one wishes to point out the fact that a person is willing to use his own body and life as a weapon, does not motivate the use of the term. A person who, in cold blood, kills both himself and others is a murderer, irrespective of what others think about and believe concerning the religious, ethical or political implications of suicide.

Certain media in the United States and other countries have begun using the correct term for these crimes: murder. Consequently, the young men and women who kill both themselves and others are homicide bombers – neither more nor less.

And those who hurt others to further their own cause do not bear responsibility, but instead blame.

February 12, 2005

Tardiness and icy roads

One of my blog colleagues, Kat, has coined a number of blog diseases, including blog neglect, blog addiction and blog blockage. To her medical blog-dictionary I would like to add the psychological malady termed blog tardiness, akin to blog neglect. Days go by and nothing gets written. This is not fair to Castor, who is supposed to be the focal point of this web page. Not only has he been neglected as far as elapsed days and weeks are concerned, I have also neglected to even mention him specifically for some time.

Today we took a stroll in the woods. Getting him ready for a hike is an onerous task. Not only is he dirty, muddy and wet when you go out to get him in the field, you also have to put studs in his shoes so he doesn’t slip on the icy roads and paths in what is often somewhat inclement February weather in Stockholm.

Studs

For those of you who don’t ride, studs in your horse’s hooves do more or less the same thing as your winter tires do for your car. Riding on an icy path without this protection is no joke. Imagine having about 1500 pounds of muscle power and skittishness underneath you, slipping and dancing nervously around on the ground. So, before you go out on a cold and sunny winter’s day, you stud (no pun intended) your horse. This entails getting out your wrench and fresh ice studs to screw into the horse’s shoes.

Chiropractor’s dream

Studding Castor is something I don’t really long to do. In all four hooves there are four screw holes with flat studs in them, flat-shaped screw heads (like bolt heads) that are there so the holes don’t get filled with a lot of dirt and grime. So first of all you have to unscrew these, clean out any sand or dirt that has got stuck underneath and then screw in the proper winter studs. Now imagine bending over, holding a hoof in the air with what feels like the whole weight of your horse pressing down on it, using your wrench to get the flat studs out before Castor gets tired of you holding his leg and decides he wants to put his foot down instead. Unscrewing the flat studs is the first job. Now that you’ve got them out and cleaned out the holes, you’ve got to put the other ones in. This takes some digital dexterity and it’s not that easy when your fingers are already getting numb from the cold air in the stable. You have to screw them in, or at least get them started, and then as quickly as possible - remember you’re still holding Castor’s leg in the air – fasten them tightly with the help of your wrench.

Then you’re all set to go.

Grass killer

If your back has taken the punishment in stride, then a brisk walk in the woods on a cold and sunny winter day is a real high. Forget about smoking grass and getting both stupid and grossly hungry. There’s no high that beats the sense of riding out on a fine day. Your back is suddenly fine again, about twenty years younger, and you’re on top of the world. The sun is shining and Castor snorts (still no pun) now and then as if to agree with you.

Since you’ve got a large animal underneath you, an animal with a will of his own, you don’t just sit back and ride. You have to communicate - around the trees, over the ditches, along the ice on the road, down the steep hill and on the path back to the stable, a route that all horses know - and tell you they know. The road back home is the best one.

Then it’s the same procedure again, with the studs, I mean. Sharp studs out and flat studs in. All part of the course.

And maybe, just maybe, part of the pleasure of it all.

Today we took a stroll in the woods. Getting him ready for a hike is an onerous task. Not only is he dirty, muddy and wet when you go out to get him in the field, you also have to put studs in his shoes so he doesn’t slip on the icy roads and paths in what is often somewhat inclement February weather in Stockholm.

Studs

For those of you who don’t ride, studs in your horse’s hooves do more or less the same thing as your winter tires do for your car. Riding on an icy path without this protection is no joke. Imagine having about 1500 pounds of muscle power and skittishness underneath you, slipping and dancing nervously around on the ground. So, before you go out on a cold and sunny winter’s day, you stud (no pun intended) your horse. This entails getting out your wrench and fresh ice studs to screw into the horse’s shoes.

Chiropractor’s dream

Studding Castor is something I don’t really long to do. In all four hooves there are four screw holes with flat studs in them, flat-shaped screw heads (like bolt heads) that are there so the holes don’t get filled with a lot of dirt and grime. So first of all you have to unscrew these, clean out any sand or dirt that has got stuck underneath and then screw in the proper winter studs. Now imagine bending over, holding a hoof in the air with what feels like the whole weight of your horse pressing down on it, using your wrench to get the flat studs out before Castor gets tired of you holding his leg and decides he wants to put his foot down instead. Unscrewing the flat studs is the first job. Now that you’ve got them out and cleaned out the holes, you’ve got to put the other ones in. This takes some digital dexterity and it’s not that easy when your fingers are already getting numb from the cold air in the stable. You have to screw them in, or at least get them started, and then as quickly as possible - remember you’re still holding Castor’s leg in the air – fasten them tightly with the help of your wrench.

Then you’re all set to go.

Grass killer

If your back has taken the punishment in stride, then a brisk walk in the woods on a cold and sunny winter day is a real high. Forget about smoking grass and getting both stupid and grossly hungry. There’s no high that beats the sense of riding out on a fine day. Your back is suddenly fine again, about twenty years younger, and you’re on top of the world. The sun is shining and Castor snorts (still no pun) now and then as if to agree with you.

Since you’ve got a large animal underneath you, an animal with a will of his own, you don’t just sit back and ride. You have to communicate - around the trees, over the ditches, along the ice on the road, down the steep hill and on the path back to the stable, a route that all horses know - and tell you they know. The road back home is the best one.

Then it’s the same procedure again, with the studs, I mean. Sharp studs out and flat studs in. All part of the course.

And maybe, just maybe, part of the pleasure of it all.

January 30, 2005

A repressive society?

Most of us reflect some time or other on our own small roles in the great machinery of the world around us. We read our newspapers, visit blogs, look at TV, surf the web and perhaps engage in some idle conversation over lunch with people we find have more or less the same outlook on life as we do ourselves. We choose our own battlefields and usually end up winning a social or political battle over people we will probably never meet or for that matter even listen to. Very few of us will put ourselves in a situation where we honestly listen to someone who has a greatly divergent opinion from our own. We act this way out of intellectual sloth and perhaps some lack of social gumption.

We cherish our individual freedoms, but don’t reflect on them very often, because most of us live in a society where we are daily reminded of our “rights” by those we have chosen to be our proxies, our elected politicians. Our representatives in government also tell us that our individual rights are inherently dependent on consensus, i.e. subjugating our own liberty for the good of others. This is the core of the welfare state, and is only possible where we relinquish our individual freedom to the – shall we say – whims of a legitimate government.

As one of my blog colleagues so wisely has pointed out, the Constitution of the United States supposedly guarantees a number of individual freedoms from the government. In Sweden we ourselves abrogate many of our own civil liberties for the government, which in turn is supposed to act on our behalf for the good of all.

That this abrogation or cession doesn’t work we can see all around us, even in the United States. There the government has instituted the Patriot Act. Section 215 of the Act modifies the rules on records searches so that third-party holders of your financial, library, travel, video rental, phone, medical, church, synagogue, and mosque records can be searched without your knowledge or consent, providing the government says it's trying to protect against terrorism. In Sweden, where a fifty percent or more rate of taxation befalls a large portion of the population, where sales taxes are twenty-five percent on most goods and where each individual’s personal ID number can be found in countless governmental and private databases, these infringements are excused by political mumbo-jumbo about the “good of all” and even worse “solidarity” a well-worn term for political repression.

Solidarity? Oh, come on.

The word solidarity entails an active choice on those involved. Solidarity by proxy is often an empty illusion, but is extremely convenient for the bolstering of political power. We saw this for example in the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe and expressly manifested in May Day parades. We see it in Sweden where the trade unions entertain an almost incestuously political relationship with the ruling Social Democratic party. We see it in the United States where anti-terrorism measures become a panacea for the adverse effects of politics engineered by a thirst for power.

In both countries, politicians use a whole battery of euphemisms in order to placate worried citizens. What is surprising is that it works, and works well. Citizens in the United States relinquish civil liberties for the protection of all. Citizens in Sweden relinquish civil liberties for the common good. The euphemisms used by our elected representatives to excuse this repression are boundless. In the US, religious catchphrases and clichés work well; in Sweden, the litanies are more secular. What is common to both societies is the seclusion of power. Politically appointed civil servants align themselves with the politically correct philosophy of power and do their work behind doors, immune to the scrutinizing of private individuals.

What it boils down to is a need for a reinstatement of a wider freedom of information and also a need for a greater opportunity of “calling” political bluffs.

Unfortunately, we don’t do this. We gripe and then sit down for lunch and gripe some more with people who agree with us. If we really listened to others, we would also be able to hear ourselves more distinctly and in turn, ask of ourselves: What is the price of my civil liberty? What is my place, my real place in the society around me? Until we do engage in this kind of intellectual decontamination we will be “blessed” with a continuing stream of power-hungry leaders, more interested in furthering their own good than yours or mine.

We cherish our individual freedoms, but don’t reflect on them very often, because most of us live in a society where we are daily reminded of our “rights” by those we have chosen to be our proxies, our elected politicians. Our representatives in government also tell us that our individual rights are inherently dependent on consensus, i.e. subjugating our own liberty for the good of others. This is the core of the welfare state, and is only possible where we relinquish our individual freedom to the – shall we say – whims of a legitimate government.

As one of my blog colleagues so wisely has pointed out, the Constitution of the United States supposedly guarantees a number of individual freedoms from the government. In Sweden we ourselves abrogate many of our own civil liberties for the government, which in turn is supposed to act on our behalf for the good of all.

That this abrogation or cession doesn’t work we can see all around us, even in the United States. There the government has instituted the Patriot Act. Section 215 of the Act modifies the rules on records searches so that third-party holders of your financial, library, travel, video rental, phone, medical, church, synagogue, and mosque records can be searched without your knowledge or consent, providing the government says it's trying to protect against terrorism. In Sweden, where a fifty percent or more rate of taxation befalls a large portion of the population, where sales taxes are twenty-five percent on most goods and where each individual’s personal ID number can be found in countless governmental and private databases, these infringements are excused by political mumbo-jumbo about the “good of all” and even worse “solidarity” a well-worn term for political repression.

Solidarity? Oh, come on.

The word solidarity entails an active choice on those involved. Solidarity by proxy is often an empty illusion, but is extremely convenient for the bolstering of political power. We saw this for example in the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe and expressly manifested in May Day parades. We see it in Sweden where the trade unions entertain an almost incestuously political relationship with the ruling Social Democratic party. We see it in the United States where anti-terrorism measures become a panacea for the adverse effects of politics engineered by a thirst for power.

In both countries, politicians use a whole battery of euphemisms in order to placate worried citizens. What is surprising is that it works, and works well. Citizens in the United States relinquish civil liberties for the protection of all. Citizens in Sweden relinquish civil liberties for the common good. The euphemisms used by our elected representatives to excuse this repression are boundless. In the US, religious catchphrases and clichés work well; in Sweden, the litanies are more secular. What is common to both societies is the seclusion of power. Politically appointed civil servants align themselves with the politically correct philosophy of power and do their work behind doors, immune to the scrutinizing of private individuals.

What it boils down to is a need for a reinstatement of a wider freedom of information and also a need for a greater opportunity of “calling” political bluffs.

Unfortunately, we don’t do this. We gripe and then sit down for lunch and gripe some more with people who agree with us. If we really listened to others, we would also be able to hear ourselves more distinctly and in turn, ask of ourselves: What is the price of my civil liberty? What is my place, my real place in the society around me? Until we do engage in this kind of intellectual decontamination we will be “blessed” with a continuing stream of power-hungry leaders, more interested in furthering their own good than yours or mine.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)